Today, I walked onto an Israeli settlement for the first time in my life, one where most of the land it stands on once belonged to my grandfather. I needed the settlers’ permission to walk onto this soil. As I walked down the sidewalk, I felt alienation and contentment all at once. The first for the utter disconnect between this land and I. The second for finally being able to set foot in a place that is rightfully mine.

"You see this hilltop? It all belongs to your grandfather.” This phrase was a recurring one on our family drives from Abu Dis to Jericho. I heard it from the first moment that I could comprehend words. I cannot even remember who said it first. But it has been a constant refrain since childhood. Even today, however, at thirty-four years old, my mother, father, aunt, and grandmother repeat the statement as if they are saying it for the first time. The repetition is an assurance, a call, to never forget. They refuse to forget. And even after so many years, I still respond with a perplexed “all of it?” as if hearing the news for the first time. I refuse to forget. “All of it.” Today, when I travel alone with no one to remind me, I repeat: "This land belonged to my grandfather."

Still, despite this historical bond with the land, despite the assurance of that history, despite the will to never forget, all that lies on that hilltop is as foreign to me as is the North Pole. Today the settler at the gate only allowed me to enter a mere two hundred yards to the police station, which sits on the settlement’s periphery, and back. He made it clear I could only spend the time necessary to finish my paperwork. I could not explore. I could not become familiar with my land. And therefore, I continue to construct my familiarity with my ancestral heritage from a distance.

As I drive by, the settlement resembles the gorgeous green fields of the luxurious Napa Valley in California. Those fields, too, are compelling, and those fields, too, are often off limits, fenced off with a sign: “Beware. Electrical Fence.” In my daydreams, I run up the hilltop of Ma’ale Adumim just as I imagined transgressing the Napa Valley fences and reveling in the green fields. In my California daydreams, I may get a citation for trespassing. In my Palestine daydreams, I may be killed or at the very least detained. There are no signs that tell me so. It is knowledge that I, like so many Palestinians, understand viscerally.

There are other reminders of California here on my grandfather’s land. Those red-tiled pitched roofs mimic the houses in suburban Fremont, where I lived for part of my adolescence. I used to sneak out the window with my cousins onto the steep roof; we gazed up at the stars and giggled about our latest crush. The possibility of being caught or sliding down and falling made it all the more thrilling. Glimpsing those same roofs lining Ma’ale Adumim, I have the urge to dismember the red tiles, one at a time, and toss them into the valley. This is not Fremont. It is my grandfather’s land.

From a distance, Ma’ale Adumim appears perfectly planned, each house a replica of the next. The homogeneity is in direct contrast to Palestinian towns, where homeowners, unbridled by urban plans, each add a bit of inconsistency to create the irrational landscape. Perhaps this homogeneity is only true for the part I can see from the road, the settlement’s oldest quarter dating all the way back to the late 1970s. Regardless of its prevalence, the pre-planned homogeneity, meant to give the sense of communal coherence, is the epitome of settler colonialism. It is colonial hegemony.

.jpg)

[Top: Ma`ale Adunim. Bottom: Silwan. Source: AP.]

“Everything must be systematically settled beforehand,” wrote Theodor Herzl in The Occupation of the Land section of his 1896 treatise, The Jewish State. The implications of Herzl’s earnest are at the root of Israel’s planning strategy. In 1948, only a few weeks following the Nakba, Arieh Sharon (not to be confused with Ariel Sharon), a Bauhaus graduate and architect, began working on a comprehensive master plan for Israel. Sharon, who was the head of the Government Planning Department at the time, worked with David Ben-Gurion and a team of European and Jewish planners, architects, and mapping experts to produce a single plan (scale: 1:20,000) for the entire state of Israel. Within a single year, Sharon and his team produced a master plan that became known as The Sharon Plan. Such scale and scope were unprecedented, as countries tend to grow over a longer period of time as opposed to cities, which are planned with such rapidness. However, Israeli leadership needed the plan quickly in order to forge the physical and developmental vision for Israel, and to ensure its control over Palestine.

The political agenda, including its time constraint, drove the development of the master plan. Thus, the outcomes of the Sharon Plan can be summarized as three-fold. First, it is an agglomeration of borrowed ideas and models, some of which were developed during the British Mandate and others taken from Europe “as ready made and abruptly naturalized.” [1] Second, the plan answered the urgent need of providing fast housing for new Jewish immigrants, especially on the borderlands in order to prevent the return of Palestinian refugees. Third, the Plan divided Israel into a number of districts that were planned mathematically, with modular neighborhoods, to house an equal number of residents. Thus, the Sharon Plan laid the foundation for the Israeli Apartheid state today: architecture that echoes European designs; peripheral settlements that enclose Palestinian towns; and “New Towns,” which are pre-planned and built in modules to facilitate rapid construction.

Less than twenty years after the Sharon Plan laid the foundation for Israel’s design, the Israeli government augmented its vision for territorial expansion. Following Israel’s victory of the Six-Day War in June 1967, the Israeli government passed legislation incorporating East Jerusalem and adjacent parts of the West Bank into Israel, thus expanding its land expropriation project and settlement expansion. In order to meet this goal, Israel pursued a number of systematic policies that would help expand Jerusalem and secure Israel’s hegemony over the City through demographic and physical control.

While Israel enacted The Land Acquisition For Public Purpose Ordinance and the Absentee Property Law, in 1967 in order to legalize the confiscation of Palestinian land and limit Palestinians spatially, Israel also put into effect a set of urban and design guidelines aimed at attracting European Jewish settlers and further displacing Palestinians. To meet these goals, Israel placed much of the land annexed in 1967 under the jurisdiction of the Israel-Lands Administration (ILA) whose management had been merged with the Jewish National Fund. The charter of the Jewish National Fund restricted the developments and use of the land to the exclusive benefits of Jews, the ILA land, constitutionally, could not be “sold or leased or used” by or for Palestinian Arabs.

Second, following the vision of the Sharon Plan for Jerusalem, the Israeli Municipality began a project of “evacuation and building,” under the pretext of “modernization,” which constituted the demolition of old Palestinian buildings, the construction of new streets, and the widening the Jaffa Street in the heart of Jerusalem. The widening of the street meant more demolitions of old Palestinian buildings. Thus, in its claim to “renew” the City, Israel erased the narrative of its Arab inhabitants.

Third, the Municipality produced design guidelines that catered to the immigrating Jewish population. For the development of many of the neighborhoods in Jerusalem, the Israeli Municipality set the height limit of buildings at six to eight stories, and required the buildings to be multi-units and “modern” looking. By modern here, I solely refer to the architectural era marked by the simplification of buildings. In other neighborhoods, Garden City patterns, borrowed from European designs of the Sharon Plan, were implemented. These designs consisted of red tiles, pitched roofs, and green spaces, and were intended to give the sense of a “planned community.”

[Modern Jerusalem. Source: jewishpostcardcollection.com, used here with permission.]

Based upon these design guidelines intended for Jewish colonial settlement of the West Bank, the Israeli Municipality rejected most plans submitted by Palestinian residents. The Israeli Municipality, considered the latter plans, usually characterized of stone-built one to two story single-family homes, as unacceptable for being “Arabic style.” Furthermore, even when the Israeli Municipality approved design plans for Palestinians, a permit could take up to four years to be issued. The Israeli authorities used this prolonged waiting period to determine if the land proposed for development could be useful for future Israeli projects. If they saw it as useful, they would apply the Public Ordinance Law, and confiscate the land for state use. [2]

I doubt my grandfather ever applied for a permit. He never had the chance.

[Traditional Palestinian Home. Image by Marcy Newman. Used here with permission.

In addition to the territorial expansion in 1967, Yigal Allon, the Minister of Labor at the time, drafted The Allon Plan to “secure” Israel’s borders. The Allon Plan proposed that Israel would hand over the Arab populated areas of Palestine to Jordan, while no Jordanian troops would be allowed to cross the Jordan River westward. In addition, the Plan proposed the creation of a “security belt” [3] of Israeli settlements along the Jordan Valley as well as a road connecting Jerusalem to the Dead Sea. In 1975, during Allon’s tenure as Foreign Minister under the first Rabin government, Israel moved to a new stage of planning and began designing the “security belt.”

Israel carried out the “security belt” urban planning strategy to preclude the expansion of any Palestinian housing construction, to implant a Jewish-Israeli population into the predominantly Palestinian population, and to further separate and segregate the Arab towns from one another. The former Director of Jerusalem District of the Ministry of Housing, Shmaryahu Cohen, summarizes the process:

We have made enormous efforts to locate state lands near Jerusalem and we decided to seize them before…the Arabs have a hold there. We all know that they remove rocks and plant olive trees instead in order to create facts in the fields. What is wrong with trying to get there before them? I know this policy is harmful to Jerusalem in the short run, but it guarantees living spaces for future generations. If we don’t do it today, our children and grandchildren will travel to Jerusalem through a hostile Arab environment [4]

My grandfather’s olive trees, on the hilltop, were creating facts in the fields.

The process of creating the security belt included building settlements on hillsides, peaks, and near important roads in the municipal areas surrounding Jerusalem. The Israeli government planned to build three settlements within this belt: Ma’ale Adumim in the east, Givon in the north, and Efrat in the south [5]. With the help of the Israeli government, twenty-three Israeli families took over my grandfather’s hilltop, marking it an Israeli settlement. Michael Dumper, a Professor in Middle East Politics at the University of Exeter, eloquently explains the location of Ma’ale Adumim in his book The Politics of Jerusalem Since 1967:

Adumim was purposely situated on an exposed hilltop overlooking the Jericho road for both security reasons and to prevent the creation of a land corridor for Jordanian access to East Jerusalem in the event of a peace agreement. [6]

The decision to build Ma’ale Adumim on the hilltop was purely political. The land of Ma’ale Adumim did not lend itself to building a town settlement, as the morphology was uneven, and a great deal of excavation and flattening would need to take place. It was, on the other hand, ideal for the building of small villages. [7]

When Thomas Leitersdorf, the lead architect and planner of Ma’ale Adumim, expressed these concerns regarding the site to Gideon Patt, the Minister of Tourism at the time, he was told that “with all due respect, this was a government decision and that in 120 days the bulldozers had to begin work on the site.” [8] Furthermore, when Leitersdorf presented location alternatives to the Ministerial Committee of Settlements, the only questions his government audience posed were: "Which of the alternative locations has better control over the main routes?" and "Which town has a better chance to grow quickly and offer qualities that would make it competitive with Jerusalem?" [9] Thus, Israel’s political decision to “grab the hilltops” overrode any site, architectural, or planning considerations.

In 1979, Israel began the construction of Ma’ale Adumim. In following with Israel’s planning strategy of producing “instant cities,” Leitersdorf and his team designed and developed the first phase of Ma’ale Adumim within three years, which included 2,000 apartments, all built on “one system of construction and infrastructure.” [10] In October of 1991, the Israeli government declared Ma’ale Adumim, with 15,500 inhabitants, “the first and largest Hebraic city in Judea and Samaria,” [11] despite the fact that it falls within the 1967 Green Line. Despite the fact that it cuts across, and onto, my grandfather’s land. The population of Ma’ale Adumim has grown from twenty-three families in 1975 to around 40,000 people today. And it is growing.

On 30 November 2012, less than twenty-four hours after Palestine gained non-member status at the United Nations, and five days after I set foot on my grandfather’s land for the first time, Israel announced its plan to build an additional three-thousand settler units. The E-1 Plan, as it is known, intends to expand Ma’ale Adumim from the west and connect it to Jerusalem, thereby accomplishing Israel’s long-term vision. It must be noted here that the expansion of Ma’ale Adumim on the east to the Jordan Valley is an ongoing process. While Israel only made the E-1 plans announcement following the UN bid, it would be naive to believe that Israel came to this decision within twenty-four hours and only as retaliation to Palestinian “unilateralism.” Israel approved the E-1 plan in 1999, but shelved it due to US and international pressure. Israel seized the moment of the UN bid to implement a plan that dates back much further than 1999.

[The E1 Plan. Source: PASSIA]

Through examining the plans and maps that Israeli leaders had drafted over the last sixty-four years, it become evident that the historical processes of settlement and road construction lead to the deliberate creation of Greater Israeli Jerusalem. The boundaries of the Greater Jerusalem Israel is currently implementing are larger than those of the Greater Jerusalem under the 1948 UN Partition Plan, which declared Greater Jerusalem a corpus separatum. The expansion of settlements both eastward and westward, as well as the creation of bypass roads, all serve to connect Israeli settlements with Jerusalemand the rest of Israel, while further dividing the Palestinian areas into pockets of lands.

[Left: Jerusalem and the Corpus Separatum, 1947. Right: Projection of Israeli Proposal for Jerusalem`s Final Status, Camp David, 2000. Source: PASSIA Palestine.]

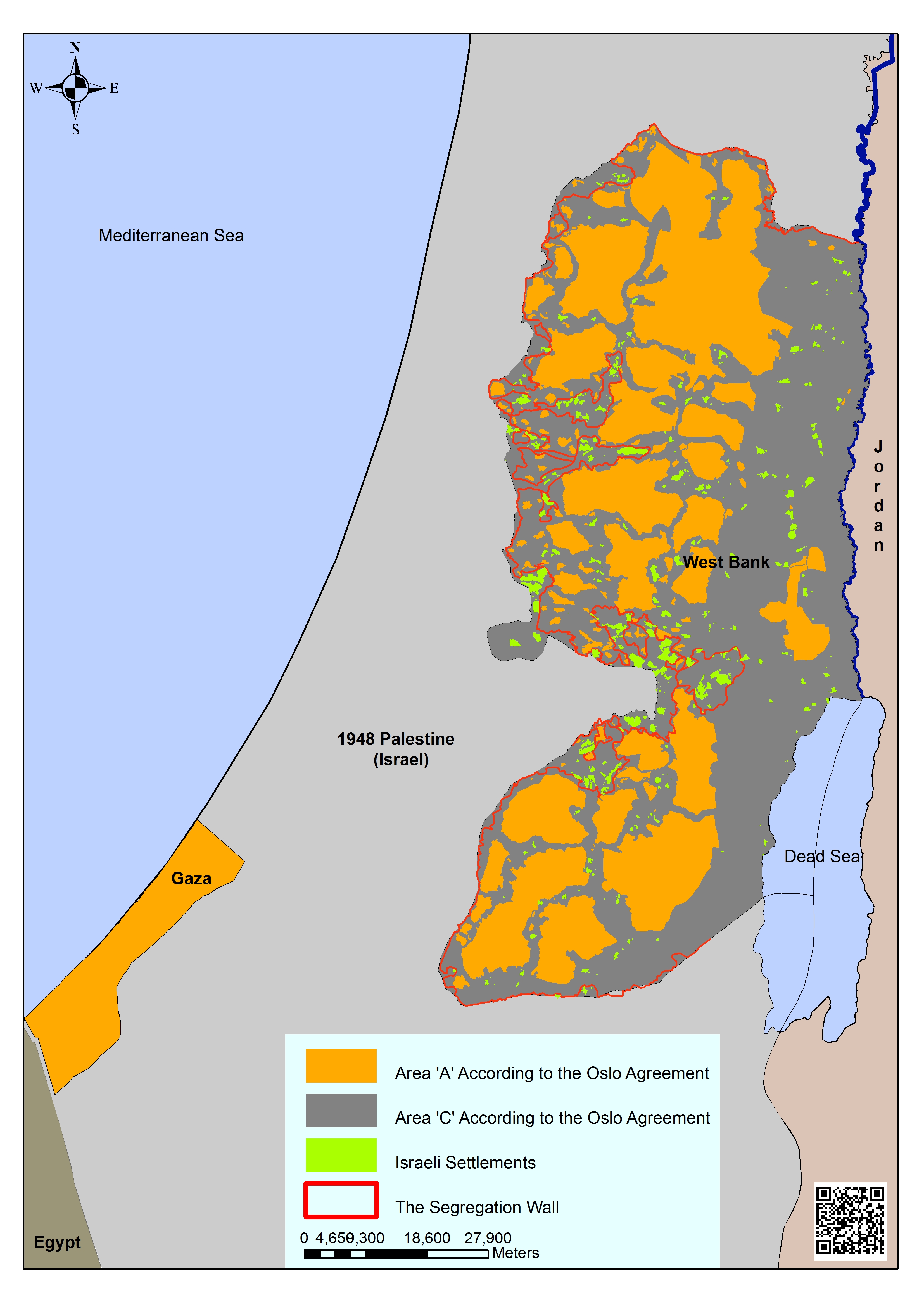

Furthermore, by comparing the Palestinian land classified as Area C, and therefore under Israeli control, under the 1993 Oslo Agreement to the Allon Plan, it becomes apparent that Area C fulfills Allon’s vision of Israeli territory within the 1967 borders. This further puts into question the viability of the US-brokered “peace process” and Israel’s good faith to establish a two-state solution. The building of E-1, which covers around 12,000 dunams, will be another step in fulfilling the Allon Plan, as it would divide the West Bank into two areas: north and south, and seal off East Jerusalem from other Palestinian cities.

[Left: The Allon Map, 1967. Source: Middle East Maps. Right: Palestine today, 2012. Source: Map by Suhail Abushosha.]

Israel refuses to leave Ma’ale Adumim isolated, unconnected, and within the Palestinian territories. Perhaps, the only way for Ma’ale Adumim to be returned to its original owners is through a one state solution. However, I know that no Israeli leader will voluntarily dismantle Ma’ale Adumim during my lifetime. It is a fortress guarding the occupiers. It is a watchtower overlooking the Jordan Valley. It is a symbol of colonial modernity. It is hegemony.

But I also know that I will never forget that the land on which this settlement stands belongs to my grandfather. A land I could have called my own. A land my children could have called their own. And I look forward to the day that I tell a daughter “You see all this hilltop? This is all your mama’s grandfather’s.”

------

[1] Efrat, Zvi, “The Plan,” A Civilian Occupation: the Politics of Israeli Architecture, Rafi Segal and Eyal Weizman, ed. (London: Babel, 2003) Chapter 4.

[2] Maguire, Kate, “The Israelization of Jerusalem,” Arab Papers, 7 (July 1981).

[3] Dumper, Michael, The Politics of Jerusalem Since 1967 (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1997)

[4] (Dumper, 1997).

[5] Following the concepts of the Allon Plan, the Israeli governments built 21 settlements along the Jordan Valley and Eastern plains between 1967 to 1977

[6] (Dumper, 1997).

[7] Tamir-Tawil, Eran, “To Start a City From Scratch: An Interview with Architect Thomas M. Leitersdorf,” A Civilian Occupation: the Politics of Israeli Architecture, Rafi Segal and Eyal Weizman, ed. (London: Babel, 2003) Chapter 9

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid

[10] Ibid

[11] Ma’ale Adumim Official Website